From a dead lake, to the largest glacier outside polar regions

By François Burgay, University of Basel

francois.burgay@unibas.ch

It was September. As soon as I stepped out of the jeep, I began walking across a vast, barren plain. Around me: a few shrubs and sand. Nothing else. It could have been any place on Earth, until a small detail caught my eye: shells. Life was here, once. It’s hard to picture this place underwater, yet just a few decades ago, at least 10 meters of water stood above my head. I wasn’t walking through an ordinary desert, but on the dried lakebed of a lake that no longer exists. I was on the arid remains of the Aral Sea, in Uzbekistan.

It might seem strange to begin a story about glaciers in a place where summer temperatures exceed 40°C. But the link is water, in all its forms: solid, liquid, and vapor. Rewinding the transformations between these states takes us not only back in time, but on a geographic journey to one of the planet’s most extraordinary glaciers, just over 1,200 kilometers from here. Today, water in this region is mostly present as vapor. Whatever remains in liquid form will likely vanish within a few decades (at least on the Uzbek side). But if, by magic, we could reverse the process, condensing all the evaporated water back onto the lakebed, we’d recreate what was once the one of the largest lakes in the world.

This mental experiment takes us back to the 1970s and 80s, when the shores of the Aral thrived with fishing activity. Moynaq, now a dusty town of barely 10,000 people, once hosted one of the largest fish canning factories in the entire Soviet Union. Roughly one sixth of all canned fish sold across the USSR came from here and other towns along the lake. Unfortunately, political decisions aimed at boosting cotton production diverted the lake’s main tributaries, the Syr Darya from the north and the Amu Darya from the south. Their waters, once feeding the Aral Sea, were channeled into cotton fields using inefficient irrigation systems that caused massive water losses. As river flow decreased, the lake slowly died, and with it, its rich ecosystem and economy.

Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the countries that once shared the Aral Sea, are largely desert. So where did all that water come from? To find out, we follow the Amu Darya southward from near Nukus, about 150 km from the lake’s former shore. The river develops through the Karakum Desert, forming borders between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, then Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and finally into the high mountains. This river has witnessed centuries of upheaval: the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the collapse of the USSR, and the birth of Central Asian republics. But the river itself remained constant, bringing water wherever it was needed. Over 2,500 kilometers later, after crossing lands of many languages and cultures, the Amu Darya finally meets his parents: the Panj and the Vakhsh rivers. From here, we enter a tangle of mountain waterways that leads us to the Pamirs, a remote, high-altitude plateau straddling Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, home to peaks like Lenin Peak, rising over 7,000 meters.

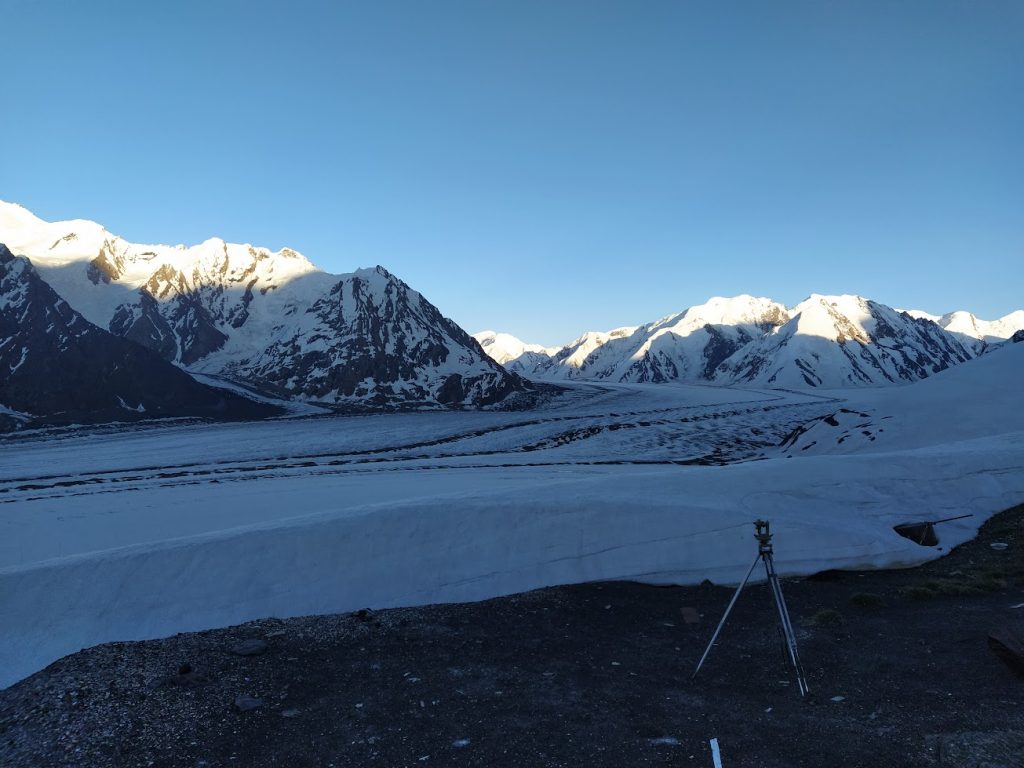

From this secluded world flows the water that sustains life for 90% of the people living in Central Asia, powering hydroelectric stations, irrigating fields, and providing drinking water. And this is where we find the final state transformation of our water: from liquid to solid. Here lies the protagonist of our story: the Fedchenko Glacier, the largest glacier in the world outside the polar regions. Officially renamed Vanch-Yakh by the Tajik government in a process of de-Russification, it stretches 77 kilometers in length, from 6,200 to about 2,900 meters in altitude. Its surface covers 700 km², about the size of New York City, and it holds around 144 cubic kilometers of ice. That’s enough to cover the entire city of Rome under a 114-meter-thick layer of ice, roughly three times the height of the Colosseum. First documented in 1878 and named after Russian explorer Alexei Fedchenko, though he never saw the glacier himself, it remained largely unexplored until 1928. That year, a joint Soviet-German expedition spent five months traversing the Alay and Pamir ranges under the leadership of Nikolai Gorbunov. A meteorological station named after him was later established close to the glacier, at 4,169 meters above sea level. It recorded uninterrupted meteorological data from 1933 to 1992. Today, it stands abandoned. A forgotten museum of Soviet meteorological research.

As a chemist and researcher, I am fascinated by Fedchenko as its ice could hold key climate records from the Pamir region. In particular, through the analysis of its ice, Fedchenko might help resolve one of glaciology’s lingering mysteries: why have many glaciers in Central Asia, unlike those in the Himalayas, grown or remained stable in recent decades? The causes of this phenomenon, known as the Karakoram Anomaly, are still under debate. While recent data suggest these glaciers are now beginning to retreat under the pressure of climate change, the reasons for the previous growth (peaking in the 2010s) remain unclear. Leading hypotheses include increased snowfall in glacier accumulation zones, greater cloud cover, or weakening of the summer monsoon, leading to cooler summer temperatures and less melting.

Nestled deep in the heart of the Pamirs, the ice of Fedchenko may hold the answers to this and other climate mysteries. For now, its waters continue their journey across deserts and plains, sustaining communities and ecosystems along their path.

The Fedchenko Glacier is our Glacier of the Month