Free K2 1990-2020

1990-2020. Thirty years have passed since our very first cleaning expedition in the Himalayas, Free K2. This article is meant to be food for thought for us all.

Copyright National Geographic Italia

Translation by Darragh Henegan

Summer 1990. A lithe figure advances, almost dancing, along the moraines blanketing the surface of the Baltoro glacier, zigzagging to the right and left to avoid the string of our porters flowing slowly toward base camp. Before long, we recognize the infectious smile of Wanda Rutkiewicz, the renowned Polish mountaineer who just summited Gasherbrum I and who now runs ahead of her expedition companions. Upon recognizing Fausto and me she shouts, “So it’s you two, incredible!” and throws her arms around us. “Free K2!” she exclaims, “After your mission, Himalayan mountaineering will never be the same again!”. We willingly accept what seems an encouraging prophecy, yet whether it will prove accurate is a different conversation all together.

Less than three years earlier, the Italian Academic Alpine Club and Banca Sella had invited a large group of mountaineers from all over the world to Biella (Italy) to take part in a major conference that the organizers hoped would mark a turning point in relations between the mountain environment and the international mountaineering community. The reason for this was alarm over the direction in which mountaineering – especially extra-European – seemed to be going, even beyond consumerist wear and tear on the mountain integrity. Many thought that the obsession with performance at all costs had begun to erode the very ideals that defined mountaineering. At the end of two days of meetings, the participants voted almost unanimously in favour of a planning document entitled “Le Tesi di Biella” (Biella Theses).

The document expressed not only hopes for the formation of a new association – to be called Mountain Wilderness – capable of waging resolute battle in the defence of the integrity of our planet’s mountains, but it also assigned that new association an initial and very precise task: to implement an exemplary “ecological” expedition aimed at relieving one of Asia’s major peaks of the tonnes of waste, altitude camps and fixed ropes left behind by countless mountaineering teams focused solely on summiting and indifferent to the fragile integrity of those extraordinary environments. In truth, the UIAA had been urging such a project for years but lacked the resolve to set it in motion.

What was miraculous was that this small, newly established association managed to do what the UIAA had failed at, despite being representative of the most prominent mountaineering clubs in the world. Just three years after its founding, Mountain Wilderness succeeded in sending an international team of mountaineers to K2, NOT to climb it up to the top but rather to restore the world’s second highest peak to its original unspoiled state. The expedition was called FREE K2 – free of the debasing wounds inflicted by the passage of various ascent teams, but also, it was hoped, of enslavement to that irreverent, aggressive and competitive mentality that ranks sporting prowess above every other behavioural or ethical imperative.

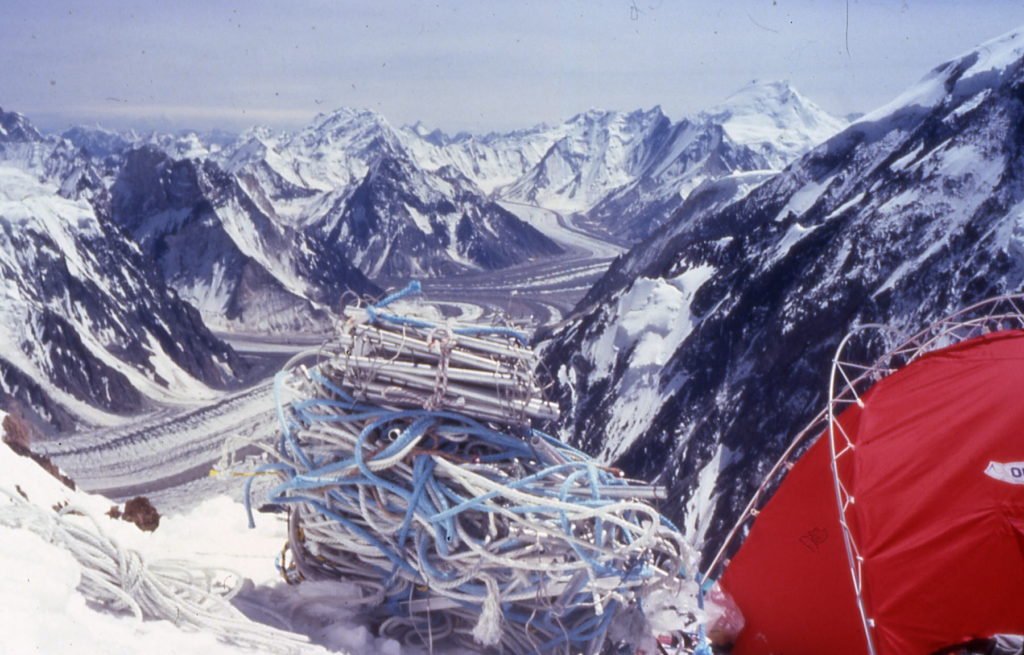

Upon arrival, the Mountain Wilderness expedition found the base camp and the Abruzzi Spur of the K2 transformed into veritable garbage dumps. It took a full month of tireless labour to liberate that great mountain, up to an altitude of 7000 metres, of all traces of human transit. More than one hundred porters were engaged to transport 2500 kilos of solid waste and over ten kilometres of fixed rope down to Skardu. Thanks not least to a film documenting it, the undertaking was a resounding international success.

The following year, the Pakistani government tasked Mountain Wilderness with organising eco-friendly mountaineering courses for the civilian and military liaison officers charged with overseeing the various foreign expeditions, whose customary tasks were extended to include monitoring visitors’ interaction with the natural environment. Not only that but, on the specific suggestion of Mountain Wilderness, the government established severe penalties for anyone who left waste behind, and made it compulsory when leaving the country to take all imported ropes back out again, placing a heavy fine on every metre of them unaccounted for. These wise provisions put Pakistan in the avant-garde in environmental protection for a number of years.

Nevertheless, the subsequent protests of the expeditions penalised, which were in turn vehemently supported by respective embassies, forced a regrettable retreat. The presence of liaison officers – now lacking in any specific training and easily cheated – was limited to the border summits (sensitive areas). In all other cases, the task of ensuring that foreign visitors did not leave their waste behind or dump it in the nearest convenient crevasse, was entrusted to local tourist agencies specialized in the arrangement of “outdoor” activities. Even a child could see the absurdity of such a system – and one that remains in effect to this day. How could a representative of agency “X”, hired by expedition “Y”, curb the behaviour of a paying customer and risk being passed over for subsequent expeditions? Thus, year after year, those heaps of trash have resumed their siege of the slopes of the Pakistani 8000-metre summits, wiping out the hopes kindled by the “Free K2” mission. So much for poor Wanda Rutkiewicz’s optimistic prophecy…

Exactly as in that past we had hoped to leave behind, clusters of fixed ropes that no one any longer feels obligated to remove sully the new ascent routes, transforming Himalayan mountaineering into a banal athletic exercise. The coup de grace came with the invasion of those commercial expeditions once restricted to the great mountains of Tibet and Nepal. The ignoble model of Everest has overflowed into Pakistan, and most specifically to the K2. Every summer, teams of Nepalese Sherpas at the service of a wealthy international clientele dutifully outfit every ascent route with fixed ropes, fully equipped high altitude camps and oxygen bottles deposits practically from the base camp all the way to the summit.

Recent and indisputable reports speak of a growing number of tents – some still in excellent condition – being abandoned at high altitude camps, along with the widespread practice of hiding refuse in crevasses so as not to have to pay few more porters to carry it down the mountain, the sale of fixed ropes lines to following expeditions and the absence of any regulation and control worthy of the name. Unfortunately, to date the government of Islamabad has not managed to muster enough national pride to at least defend Pakistan’s highly emblematic K2 summit from such mercantile servitude.

Is there any reason to hope that they will?

The problem is not limited to individual mountains, but also deeply concerns the routes leading to their bases and involves not only solid waste dumping. It must be remembered that the K2 pyramid rises at the end of the Baltoro glacial valley, which is the obligatory itinerary for anyone wishing to reach also the other three most popular “eight-thousanders”: the Broad Peak, the Gasherbrum 1 and the Gasherbrum 2. As a result, during climbing season, the anthropic pressure along the Baltoro has reached unsustainable levels and is causing the rapid decay of the natural environment and ecological patrimony of the entire area. Not only and not so much as a result of the abandonment of non-biodegradable refuse, but more of the human excrement scattered everywhere in the vicinity of rest areas or “stowed” in grim and largely ineffectual concrete latrines. Suffice it to think that every mountaineering expedition, especially commercial ones consisting more or less of ten paying participants, engages no less than 100 porters, and that every member of a trekking excursion is assisted by four or five porters. Over recent decades, an average of approximately 1000 foreign mountaineers and excursionists reach the Concordia confluence at the head of the Baltoro glacier annually. The results are easy to compute. Some time ago the Pakistani Ministry of Culture and Sport calculated that during the summer months each rest area along the Baltoro would have to be able to handle the impact of approximately 20,000 people (foreigners plus porters), between those going and those coming; 20,000 transiting through each rest area equals, more or less, fifty tonnes of excrement per site per season. The sewage system capable of handling an avalanche of such proportions – especially in areas short on water resources – has yet to be invented.

Anyone who walks across the Baltoro today runs into a sea of human waste, with or without those little sheets of toilet paper that signal the passage of foreigners; not to mention the crushing impact of the troops that for decades have been patrolling the ridges bordering on the Indian Karakorum. Ever greater numbers of trekkers return home with complaints about the constant stench that by now envelopes the entire route – not to mention the reeking army mule carcasses left to rot along the moraines.

Mountain Wilderness has been trying for years to convince the Pakistani authorities to resume the struggle against this lethal decline and put things back on the track they were on after 1990s by reinstating the role of well-trained liaison officer/mountaineers, reintroducing heavy fines for untoward behaviour and drafting strategies and incentives aimed at orienting the flow of foreigners toward areas other than the Baltoro.

Although somewhat less celebrated, the Western Karakorum, Hindu Kush, Hindu Raj and Swat ranges offer equally captivating peaks, just slightly lower in altitude and sparsely visited, where it is still possible to have an authentic encounter with the vast and uncontaminated Asian mountain environment. A more carefully considered distribution of visitors would allow nature to metabolize the physiological traces of human transit without being damaged and, even more importantly, would restore to the Himalayas at least a part of their original explorative vocation.

What is the point of a mountaineering stripped of adventure? Must eradication of the blind arrogance of commercial enterprise really remain a mere utopian quest?

Carlo Alberto Pinelli