Beijing 2022

When a lack of snow threatened the 1964 Olympic Games in Innsbruck, the Austrian army rushed to the rescue, carving out 20,000 blocks of ice from the mountain side and transporting them down to the luge and bobsleigh tracks. They also carried 40,000 cubic metres of snow to the Alpine skiing slopes and left 20,000 cubic metres of spare snow as a back-up.

Climate change is making artificial snow increasingly critical for the Winter Olympics and winter sports more broadly. The 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid was the first one to use snow machines, but more recent Games have been especially reliant on them: 80 percent of the snow at the Sochi games and 90 percent of Pyeongchang’s snow came from machines.

What is artificial snow, anyway? To make snow, a machine mixes water with compressed air and shoots out the mixture at an angle; the water freezes on the way down, resulting in the white cover we see on the slopes.

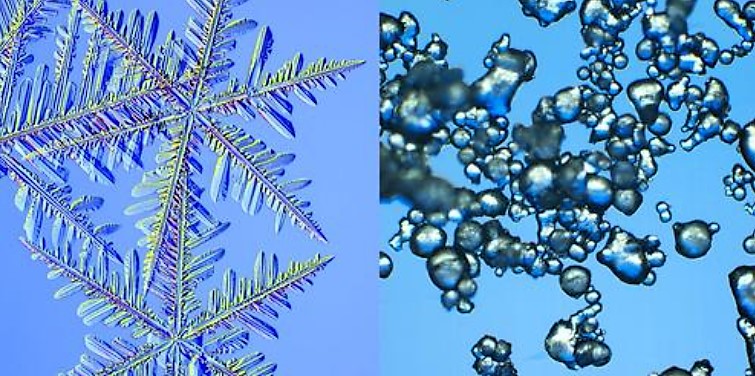

“Natural snow and artificial snow formation are totally different processes,” says Kenneth G. Libbrecht, physicist. Natural snow crystals begin with a tiny droplet of water only a few microns wide, Libbrecht says, which forms around a nucleus like a speck of dirt or dust in the air. Snowflakes often take about an hour to grow from the inside out, as the nucleus absorbs water vapor from the air around it to create a perfectly symmetrical fractal.

Researchers at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, reported that of 21 Winter Olympics cities, only one would be reliably cold enough by the end of the century, if global greenhouse gas emissions remain on the current trajectory.

A “joyful rendez-vous on pure snow and ice”, was the promotional slogan of Beijing’s bid to host this year’s Winter Olympics. And there was every reason to believe the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics could be completely devoid of natural snow, which is why the slopes were filled with huge quantities of artificial snow, giving them the appearance of white ribbons on a brown backdrop. Against all expectations, Sunday brought heavy snowfall in the city and near-blizzard conditions in the mountains.

Artificial snow comes at a huge monetary and environmental cost. China estimated the Winter Olympics will need about 49 million gallons of water (185 million litres) to make its snow; experts think the Games will need 10 times that amount.

While Chinese officials say the 2022 Olympics will be the most sustainable ever, pointing to the widespread use of renewable energy, hydrogen-powered vehicles, and pre-existing venues and have pledged to reuse the meltwater once the Olympics end, a report from the IOC says that Chinese officials have underestimated the amount of water that would be needed for snowmaking and overestimated the ability to recapture water used for snowmaking.

Snowmaking for the 2022 Olympic Games has reportedly resulted in water being diverted away from local residents and farmers, who are already short of this resource as Beijing suffers from an endemic water shortage. Artificial snow also destroys native vegetation and can cause erosion and landslides, exacerbating the heavy environmental impact of constructing ski runs in natural landscapes.

If the Olympic venues of Beijing 2022 are converted into permanent ski resorts as planned, these unsustainable practices will likely continue long after the games. And we should not forget that the area falls within the core area of the 4,600-hectare Songshan National Nature Reserve, some of which was taken “to provide the necessary space for local sustainable development and to promote interaction between ecological protection and economic society” as the deputy mayor of Yanqing said, the county in Beijing that has jurisdiction over the Songshan National Nature Reserve.

But sacrificing biodiversity to ski runs “is standard form for the Winter Olympics. Vancouver 2010 built over sacred indigenous lands. More than 80% of the mountain venues for Sochi 2014 fell inside Russia’s protected Sochi Natural Park and Sochi State Natural Reserve, until their boundaries were entirely redrawn to accommodate ski jumps and hotels. Pyeongchang 2018 required the cutting down of thousands of ancient trees on Mount Gariwang, itself a sacred site in South Korea.

The IOC’s Get Out of Jail Free card for all of this deforestation, and for the soaring carbon emissions incurred in each Olympics, is its promise that the games will be carbon zero, perhaps even carbon negative. That claim is based on the purchase of carbon offsets in the form of investments in the Great Green Wall of Africa. The Green Wall is an African Union project to create a transcontinental 15km-wide strip of forest along the southern edge of the Sahel, from Senegal to Ethiopia, sucking up carbon from the atmosphere and halting the southward spread of the Sahara desert.

It is an admirable vision, desperately underfunded, administratively fragmented, and fiendishly complicated to actually make work on the ground. After almost 20 years, less than 5% is complete. The IOC is kidding us and itself. Even were its small investments to prove productive, the carbon absorption that new forests bring will not happen for another 30 years, by which time the winter sports extravaganza that funded it, and the industry it promotes, may have been consigned to climate history.” *

*David Goldblatt, www.opendemocracy.net/en/beijing-2022-winter-olympics-artificial-snow/